|

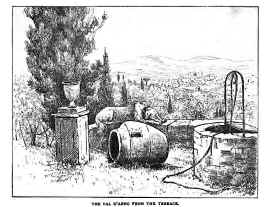

Continued from the previous page. Only one small villa lies beyond it; then nothing but olives and corn, and one or two scattered cottages, right up to the crest of the hill above Compiobbi. There, by a ruined chapel of the Holy Cross, where a few cypresses point to heaven, you overlook another reach of the Arno, a cluster of picturesque villas, crowding summits, and the dark woods of sweet Vallombrosa nestling in the folds of the hills below the sun-baked curves of the Consuma Pass. In searching for local romance we learnt that the archway spanning the little lane at our gates was supposed to be haunted by a spinning ghost, and that the country folk did not willingly pass through it after dark. It was disappointing to be also told that the legend originated in a trick played by a boy years ago, and recently confessed by him to the owners of the Gamberaia. But superstition is hard to kill, and the Settignano peasantry cling to many primitive beliefs. They place rosemary in their windows to keep away evil spirits; they prefer the charms and nostrums of a wise woman down in the valley to the scientific treatment of the local doctor; and they ascribe cholera and all epidemics to the effect of poisons willfully scattered by government agents. Settignano itself is a delightfully pretty and well-to-do village, or rather - I beg its pardon - fraction of the township of Fiesole. The road to it from Florence has no suburban ugliness. It winds through fields and vineyards, and climbs the ascent among the olives with no walls to impede the spreading view over hill and valley. Runlets of clear water trickle down beside low hedges of sweet-briar; poppies and gladiolus and love-in-the-mist are ready to your hand among the corn, and brown-roofed farms emerge from a sea of greenery. The carriage road proper ends on the triangular piazza, where a realistic statue of Tommaseo suggests sympathy with modern thought, and a much-mutilated monument to Septimius Severus records the mediaeval belief that that emperor was the founder of Settignano. As a matter of fact, it can boast a far older origin, on the testimony of ancient inscriptions that have been dug up close by. One rough, paved track leads through the village to an outlying mountain hamlet, another dips down to the Gamberaia. The people of Settignano are thriving and energetic. They have a little open-air theatre where performances are often given, and they are slowly erecting another on a more ambitious scale. They still preserve traditions of art; and if no great sculptors are born among them as in the days of Desiderio da Settignano, or their foster child, Michelangelo Buonarotti, they have an inherited facility for working in stone and marble. They are also very skilful in Florentine mosaic, and nearly every house has its wheel and bench for the cutting of gems. The big mosaic manufactory near the Villa Michelangelo has given much development to this delicate industry. The church is not interesting. It has a curious old pulpit of grey granite, but its many pictures are below mediocrity. But the neighbouring chapel of the Misericordia contains one of Desiderio’s best works, a bas-relief of the Madonna and Child executed in his daintiest style. But the artists of Settignano must not make me forget the musicians of the Gamberaia. Spring was late, and the nightingales were still in full song towards the end of May. They dwelt in the ilex groves, and never elsewhere in one place, I knew so many nightingales. Their jocund voices gladdened our days and nights. We seldom saw “their bright, bright eyes,” but even in the stillest hours of hot summer noons there was always a pleasant domestic stir among the nests over-head in the thick green foliage. And about an hour before midnight their evening concerts would begin. But as time went on their tuneful voices were less often heard. Even nightingales are oppressed by family cares, and, like young ladies, apt to give up their music after they are married. The blackbirds, however, were untiring singers, and continued to greet us with their sweet if flippant love duet. One sings, "Ben mio ti vedo;" the other replies, "Setu mi vedi, vkni a me” — “I see thee, my sweet.” “If thou seest me, come to me.” But in English the words scarcely fit the pretty strain. The passage from spring to summer was a leisurely pageant this year. When first we came to our Tuscan villa the fields were fringed with the azure flames of the scented iris; we saw the corn plots change from blue to yellow-green, and then to tawny gold; we saw haymakers tossing the fragrant grass that was all ablaze with poppy and gladiolus; and we saw the long swathes of bearded wheat fall before the reaper’s sickle. The clamorous cicale sawed all day, as though grinding the heat; crickets chirped all night; hot mists rose from the plain; summer lightning flashed from the skies; and the last fireflies — they go with the corn — wove their gleaming devices in the air. The starlit terrace became our evening saloon, and the songs of the young girl with the guitar leaning against the stone lion on the wall were often interrupted by the cry of the screech owl or the softer note of the dark bird that flew so heavily down from the roof to the olives below. But all things must have an end, and just as the young swallows were learning to fly, we looked our last on the glittering, bright city and dusky hills; and then in the haze of early morning drove down our cypress avenue, bound for wind-swept heights long miles away from Villa Gamberaia. More about Villa Gamberaia and the gardens of the Tuscan villas. |