|

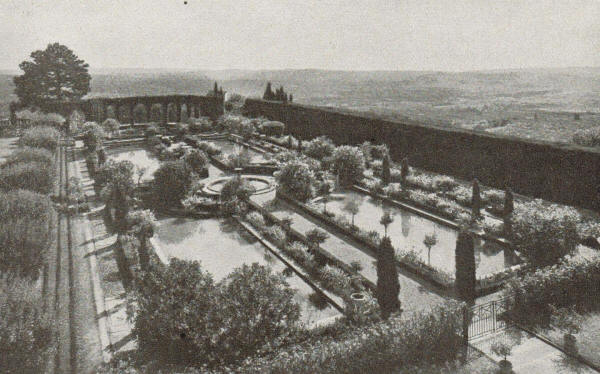

This is the first chapter of Sig.ra Villari's book, devoted to a rather florid description of Villa Gamberia. The garden of Villa Gamberaia as it was in 1934 On a spur of the steep hillside beyond Settignano, four miles to the north-east of Florence, stands the Villa Gamberaia. It is a sturdy, oblong mansion, facing the western sun. It is two-storied, brown-roofed and its lower windows are sternly barred. From either end of its eastern front, balconied arches stretch out like arms and lead by hidden stairways to the chapel at the comer of the avenue and the garden on the southern side. And though these arches are plainly an after-thought, and out of harmony with the grand severity of the main building, they are not unpleasant to the eye, and add to the quaint charm of this rural palace. The Gamberaia is a typical villa of the late Renaissance period, and its founder, Messer Zenobio Lapi, whose grim portrait decorates the saloon, must have been a man of lordly tastes as well as substance. No position could have been better chosen, no outlay spared in planning its groves and gardens. It clings midway on the olive-clad slopes rising from the basin of the Arno to the pine-fringed ridge that sweeps round from Monte Ceceri to Compiobbi; and its ilex woods and cypresses interrupt the soft monotony of the grey-green foliage above and below its terraced walls. It is approached by a precipitous lane from Settignano; a range of giant cypresses guards its gates, and it has an avenue of the same trees flipped to a broad flat surface about ten feet from the ground. There is a great grass terrace before the western front bordered by a low wall set with stone dogs and lions, and commanding a glorious prospect. You look down on the City of Flowers across a sea of greenery - olives and vines and gardens and cornfields; you see all its gracious coronal of tower-capped hills, its branching valleys to the south, a stretch of plain dotted with towns and villages innumerable, a gleam of the river here and there, and curve beyond curve of mountain lines, crowned by the translucent Carrara peaks and the advanced guard of the Central Apennines still whitened by lingering snows. In the foreground to the right, across an interval of olives and corn, a white-belfried church crowns the hill of Settignano; while the .pine-clad ridge beyond, and the amphitheatre of Maiano, with the massive tower of Mr. Leader’s villa below Vincigliata, are delightful details of the middle distance. And this view, beautiful as it is in mere outline, wears a different charm at every hour of the day. In early morning, Florence is a faintly tinted bas-relief against a background of vaporous hills; towards evening its domes and cupolas are as dusky jewels set in a verdant cup ; at sunset it is flooded with golden light, while the sky to the south and east is luminous sea-green or delicate blue besprinkled with carmine cloudlets fading to ashes of roses. Or perhaps storm banners are abroad, and the lurid orange light to the west is barred with black and grey. Our sky scenery is ever new, just as the fleeting cloud-shadows for ever change the face of our hills. Dearest of all moments, perhaps, is when the after-glow has burnt out and the value of every mountain line is clearly defined, and pine and cypress are intensely black against the sky. For then the great dome of Santa Maria del Fiore assumes a gloomy grandeur. Florence is a city of mystery, and you scarcely rejoice when gleaming chains of yellow light again transform it into a smiling abode of men. Neither from Bellosguardo nor Fiesole nor other well-known posts of vantage does Florence wear so pictorial an aspect. No meanness of modern stucco, no cross lines of chessboard streets are visible from this Settignano hillside. Beyond olives and vineyards you see the city clasping the river, worthily crowned by Brunelleschi’s dome and Arnolfo’s tower, and with all lesser spires and belfries grouped in graceful order. From the garden of Villa Gamberaia towards Florence But this grand outlook is not the only charm of our Gamberaia. The house itself is an ideal summer abode, with great vaulted rooms round a cloistered court, whence a doorless stairway on either side gives straight, steep access to the upper floor. The lofty entrance-hall looks to the west, and measures about eighty feet by thirty. This also opens on the courtyard in a straight line with the eastern gate-way, so that a fine current of air is always to be had. Its scanty furniture is in keeping with the architecture: straight-backed chairs and huge tables of mediaeval build, and great battle-pieces and portraits by old, if deservedly unknown artists. Sundry mysterious recesses and secret stairs in the walls are suggestive of past romance, and from one of the enormous cellars stretching under and around the house runs a subterranean passage communicating with the upper garden. This, however, has been long blocked up. Several of the doors are surmounted by Latin inscriptions, setting forth how the mansion was built in the year of our Lord MDCX, by Ser Zenobio Lapi, and how it was enlarged and completed by his descendants some fifteen years later. After changing hands several times, it became a possession of the Gondi, then passed to the Counts Capponi, who sold it to a French gentleman, to whose family it still belongs. It is said to have been a Medici villa, but the well-known balls are absent from the various escutcheons on the walls, and there is no historic record of their ownership. It is true that a Gamberaia was numbered among their estates, but there are three other villas of that name in the neighbourhood of Florence. Even the derivation of the word is uncertain. Some say that the ground was once held by the Gamberelli family; others that a little lake formerly existent in the valley below and well stocked with gamhere (crayfish) was the origin of the title. The only historic personage who has any discoverable connection with the Gamberaia is one of our own times. Napoleon III. inhabited it for some months when he was Prince Louis Napoleon. His father lay ill in Florence and for political reasons he was not allowed to reside in the city. He must have known sounder slumber in the quiet yellow chamber to the south than he ever slept afterwards amid the imperial splendour of the Tuileries. Whether the Medici had a hand in them or not, certainly the grounds of the Gamberaia were planned on a princely scale, and with various dividing walls and stout iron gates that, together with the secret passage, show a princely regard for personal safety. The eastern front looks on a narrow lawn nearly four hundred yards in length. At one end, behind neglected rose-beds, broken fountain and rockwork, rises a screen of mighty cypresses a hundred feet in height. At the other, is a statue-decked balustrade overlooking a billowy sea of olives, a reach of the Arno, and a delicate interchange of hill and valley. This long stretch of lawn is one of the prides of the Gamberaia. No other villa far and near can boast so great an extent of level space, and beyond the vase-crowned wall of the upper garden, it is bordered by a close box hedge, on which three persons might easily lie abreast. “God Almightie first planted a Garden. And indeed it is the Purest of Human Pleasures. It is the greatest Refreshment to the Spirits of Man.” Thus Lord Bacon, and there was much at the Gamberaia to remind us of the statesman’s ideal pleasaunce. For it is duly divided into three parts, and has a “greene” at the entrance, alhough of far smaller extent than the four acres prescribed by our author. Likewise, it has two fair alleys of grass hedged with clipped box and cypress that give out their fragrance to the sun; and, instead of covert alleys, has groves of ancient ilex trees with gnarled and twisted trunks. One of these lies open to the east and “looks abroad into the fields,” and over rolling olive slopes to the turn of the hills by Compiobbi. It has evergreens “rounded like Welts,” though these have expanded in course of years into monstrous globes of foliage. And in the middle of the main garden, where vines and vegetables, fruit-trees and Egyptian wheat are bordered with pink and red roses, there is a fountain where Cupid on a dolphin “sprinkleth water” on the goldfish below, and can on occasion shoot jets of spray almost as high as the eaves of the house. Villa Gamberaia in the evening light Across the grass, and directly opposite the eastern door, is a narrow enclosure of the true rococo style. It has miniature flower-beds and paths; a fine oval fountain of granite, with graceful handles, set in a circular carved basin, decorates the alcove at its end. Stone deities and troubadours are set in niches round its walls and draped with climbing weeds, while two dainty flights of steps on either side communicate with the ilex wood and the upper garden. Great bushes of lavender guard these steps with their fragrant spikes, and roses lean down from the trellised arbours that are thr entries to the treasury of flowers above. For there, lilies and carnations, heliotropes and geraniums are ranged in tempting order, and, with hundreds of lemon trees in huge earthern vases, crowd the air with a symphony of scent. Pomegranates are putting forth their buds of flame, and the rose-oleanders coming into bloom by the wall that is crowned with tall white lilies. Here, too, is a large fountain with a "fair receipt of water,” peopled with goldfish and over-grown with water-lilies. And when the sun beats too fiercely on these flowery terraces, a gate by the empty orangery leads to the second ilex wood, where the light plays pretty tricks among the glossy leaves, and you look down a vista of twisted trunks to an open space, framed in dark greenery, that might well serve as the set scene of some classic idyll. And by this cool descent you find your way, through another gate, back to the long lawn by the rose- festooned cypress trees. This summer Paradise, musical with bird voices and the hum of bees, is as secluded from the world as if forty miles, instead of four, divided it from Florence.

More about Villa Gamberaia and the gardens of the Tuscan villas. |